Can Africa ever unite? This question has perplexed generations across the continent for over seven decades.

The formation of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) on May 25, 1963, was driven by the core mission of

fostering African unity. Yet, 62 years later, Africa appears more fragmented than it was in 1963. To suggest that Africans have ignored this call for unity would be an injustice to history. Kwame Nkrumah dedicated his life to

the vision of a “United States of Africa.” Following his death in 1972, a leadership vacuum emerged, briefly filled by Muammar Gaddafi in the early 21st century. Tragically, his death marked the end of a significant chapter in the pursuit of African unity.

Ironically, while the pan-Africanist movement continues to gain traction across the continent, it is often foreign powers that treat Africa’s 54 nations as a single entity during summits like Turkey-Africa, Russia-Africa, or

UK-Africa gatherings. This raises a critical question: why, more than six decades after the wave of independence, is Africa closer to fragmentation than unity?

A Continent of Diversity

Most countries in sub-Saharan Africa are not homogenous; they comprise diverse ethnic groups within their

borders. This contrasts sharply with nations like Japan, Bangladesh, or China, which are predominantly composed of a single ethnic group. Africa’s diversity is evident in the multitude of languages spoken within individual

nations, a factor that often fuels civil unrest. This phenomenon was initially exploited by colonial powers

through their “divide and rule” tactics and later perpetuated by post-independence leaders.

These internal divisions make it challenging for some African populations to prioritize national or continental

unity over tribal affiliations. While such divisions are not unique to Africa, they are deeply entrenched in many

societies across the continent, rendering the dream of continental unity elusive. To overcome this, individual

nations must first foster a sense of national unity, prioritizing collective identity over ethnic loyalties. Rwanda

and Tanzania stand out as success stories in this regard, offering valuable lessons for the continent.

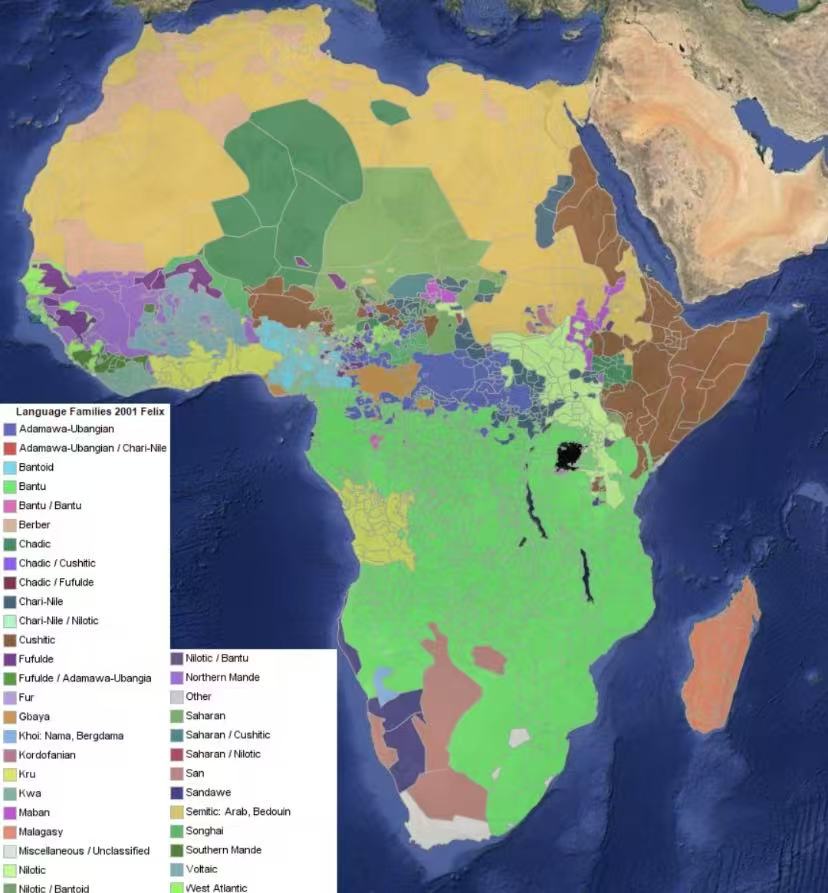

A map of Africa showing the various ethnic groups.

Disunity in Unity

Despite the internal divisions plaguing many African countries, remarkable efforts toward unity have been

made at the continental level. Central to these efforts is the establishment of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU), now the African Union (AU). The AU has served as a beacon of African unity, demonstrating how

continental systems can benefit over 1.2 billion Africans. Institutions like the Africa CDC and the African Development Bank exemplify how a united Africa can manifest through robust organizations. Regionally, bodies such as the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), the East African Community (EAC), and the

Southern African Development Community (SADC) promote unity by fostering free trade and, in some cases,

political integration, such as the proposed East African Federation within the EAC.

However, this is where the momentum for unity often falters. For instance, ECOWAS currently operates without three member states—Niger, Mali, and Burkina Faso—due to tensions over their military-led governments.

Some analysts suggest that ECOWAS leaders opposed these juntas to deter similar military takeovers in their

own countries. As ECOWAS marks its 50th anniversary in 2025, these three nations, though invited, declined to participate, highlighting the fragility of regional cohesion. Ironically, the Alliance of Sahel States appears more

organized and united than some larger regional blocs, proving that African unity hinges on policy alignment

rather than sheer numbers.

A recurring challenge within these organizations is the perception of domination by economically and politically stronger nations. In SADC, South Africa often takes the lead; in ECOWAS, Nigeria and Côte d’Ivoire dominate;

and in the EAC, Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda overshadow newer members despite the bloc’s expansion to eight countries. This creates a facade of unity, where nations with greater economic or military power wield

disproportionate influence, undermining the principle of equal representation.Funding further complicates the functioning of these multilateral organizations. Many rely on cofrom a few nations, while others consistently

fail to meet payment deadlines. In the EAC, for example, Kenya, Rwanda, and Tanzania make timely

contributions, whereas Burundi and South Sudan often fall behind. This creates significant funding gaps in

regional bodies, which could escalate into financial challenges if continental unity is achieved. Such gaps invite

external funding—and influence—a scenario that pan-Africanists and leaders vehemently oppose.

As investigative journalist David Hundeyin noted, “African countries fund only about 15% of the AU’s annual

budget. The remaining 85% comes from the EU, multilateral organizations (essentially the U.S. government

through intermediaries), and, to a lesser extent, China. That’s why the AU passport, slated for launch on January 1, 2014, remains unrealized 11 years later. The AU serves those who fund it, not Africans.”

For the dream of continental unity to become reality, critical issues must be addressed: sustainable continental funding, equitable power and influence among nations, and respect for each country’s internal affairs.

Too Focused Abroad, Too Detached Within

African content creators like Wode Maya have highlighted the challenges Africans face when traveling within

the continent, particularly with African passports. Exorbitant visa fees, even between neighboring countries, are a significant barrier. For example, the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) offers visa-free access to only six

African nations, while citizens of neighboring countries like Uganda, Zambia, and Angola face fees of

approximately $100. Historical political tensions may explain the exclusion of nations like Uganda and Rwanda, but similar restrictive policies persist in Angola, Algeria, Ethiopia, Egypt, and South Africa, even when relations with neighbors are cordial.

There is cause for optimism, however. Countries like Rwanda, Seychelles, and Benin have opened their borders to all Africans with visa-free access, setting a positive example. Greater freedom of movement across the

continent could drive economic investment and tourism, yet many African nations remain hesitant to embrace

this approach. Strikingly, colonial powers like Britain, France, Spain, Belgium, and the United States often face

fewer visa restrictions when traveling to African countries, reaping the economic benefits of easier access.

Namibia has taken a bold step by imposing visa fees on nations like the U.S. and U.K. that do not reciprocate its visa-free policies, but most African countries appear reluctant to follow suit, fearing economic or diplomatic

repercussions.

Who Are We?

One of the most profound unanswered questions on the continent is: What makes us African? Is it our race, our nationality, or simply our presence on the African continent? In parts of Arab North Africa, some perceive themselves as more Arab than African, often due to their lighter skin tone. A striking example occurred during the

2022 FIFA World Cup when Morocco reached the semi-finals. Initially, the achievement was celebrated as a

victory for the Arab world, despite Morocco’s membership in the Confederation of African Football. While

Moroccan players later emphasized that it was also an African triumph, the initial narrative revealed a deeper

identity divide.

Contrastingly, conversations with Zimbabweans reveal a different perspective. They describe how white

Zimbabweans passionately discuss the hardships facing ordinary citizens, often expressing greater concern for

the nation’s economic and political future than some of their Black counterparts. This shared reflection on

societal challenges transcends skin color, highlighting a sense of national identity rooted in shared experiences.

This raises a critical question: Who is African, and what defines our African identity? What binds us to the

continent? The sooner Africans resolve this question, the faster the path to unity will unfold.

The Final Take

For Africa to unite, these bottlenecks must be addressed. As 2063 approaches—marking the African Union’s

centenary—the continent we leave behind must not be as divided as it was in 1963. Despite our hopes, the

persistent challenges of neo-colonialism, poor leadership, a lack of common identity, and prioritizing

nationalism over continental unity continue to hinder progress. Africa’s time for unity is now—not in slogans or speeches, but in the collective heartbeat of the 1.2 billion people who call this continent home.

Written by

Rugaba John Paul

Sangyin Journals

Awesome https://lc.cx/xjXBQT

Good https://lc.cx/xjXBQT

Good https://lc.cx/xjXBQT

Very good https://lc.cx/xjXBQT

Interesting article

Dear,

Thank you for this powerful and necessary narrative about our dear Mother continent that continues to bleed and cry out for help from her inhabitants. You will agree with me that Africa has a chronic problem, a problem that seems to be incurable at this moment and time. There was indeed a time during the period of liberation struggle that the continent was more united both at a national and continental level. Where we find ourselves today is not only concerning but scary. The reality and fact, however, on the Mother continent is that of greed, corruption (sometimes) incompetent, careless and misleading leadership. Frankly speaking the continent has no leadership and that is where we need to start. Shameless and corrupt leaders outnumber the few good (if any). Therefore, Young Africans should unite from north to south and east to west to fight for their continent, even if it means revolutions.

Good https://urlr.me/zH3wE5

Awesome https://urlr.me/zH3wE5

Good https://rb.gy/4gq2o4